I remember reading The Glass Menagerie in high school. At what point in high school, and whether it made an impression on me, I don’t recall. But I don’t think I ever read anything else by him before being given the gracious opportunity to review DBS Publications LLC’s fine press edition of Tennessee. I don’t read a lot of plays but love when I run across one by a master of drama and language like Tennessee Williams. The DBS edition contains three volumes, including two popular plays Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and The Glass Menagerie, and one recently discovered play These are the Stairs You Got to Watch. So this was a great opportunity to reacquaint myself with Williams as well as read some of his other plays. For this review, I’m going to concentrate on the first two plays.

I remember reading The Glass Menagerie in high school. At what point in high school, and whether it made an impression on me, I don’t recall. But I don’t think I ever read anything else by him before being given the gracious opportunity to review DBS Publications LLC’s fine press edition of Tennessee. I don’t read a lot of plays but love when I run across one by a master of drama and language like Tennessee Williams. The DBS edition contains three volumes, including two popular plays Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and The Glass Menagerie, and one recently discovered play These are the Stairs You Got to Watch. So this was a great opportunity to reacquaint myself with Williams as well as read some of his other plays. For this review, I’m going to concentrate on the first two plays.

In his preface, Michael Khan says

“…Tennessee is both a great storyteller and an extraordinary poet who uses language more beautifully than any other American writer. His plays are incredibly emotional, extreme, and extravagant. They are Southern Gothics told with amazingly ravishing language that is unlike anything else.”

“…Tennessee is both a great storyteller and an extraordinary poet who uses language more beautifully than any other American writer. His plays are incredibly emotional, extreme, and extravagant. They are Southern Gothics told with amazingly ravishing language that is unlike anything else.”

I have to agree with him. And he goes after issues and emotions that are difficult to express for most of us, and probably for the actors as well. Even today I expect the actors find it difficult to perform the roles well and readers and theatre-goers are still disturbed by the plays. So I imagine the reactions were even more extreme when they first appeared. Tennessee wrote during the 40s and 50’s when these issues weren’t talked about in public. Kahn sums up Williams’ plays as being about “…the vagaries of the human heart and the psyche, and triumphs—or failures—of people over adversity.”

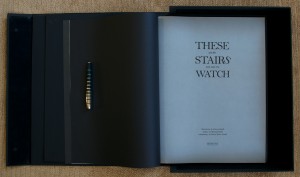

Also included in this edition is commentary by Smith in the form of an imaginary interview with Tennessee. Both the preface and the interview are printed in the beginning of the first volume, These Are the Stairs You Got to Watch, as well as being printed separately and inserted into the solander box. The preface was well worth reading and the interview was an interesting and imaginative view of the author.

Also included in this edition is commentary by Smith in the form of an imaginary interview with Tennessee. Both the preface and the interview are printed in the beginning of the first volume, These Are the Stairs You Got to Watch, as well as being printed separately and inserted into the solander box. The preface was well worth reading and the interview was an interesting and imaginative view of the author.

Throughout the plays, I found Tennessee’s stage notes fascinating. In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, he states that the room the set should try to create “…must evoke some ghosts; it is gently and poetically haunted by a relationship that must have involved a tenderness which was uncommon.” And in suggesting the lighting, he mentions a photo he once saw of the veranda of RLS’ veranda in Samoa that had a quality of “tender light on weathered wood.”

In Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, we have a southern plantation family coming apart as the patriarch, who built up one of the finest plantation in the South by sweat and grit, slowly dies from cancer. Those soon to be left behind are maneuvering for power and for gain as the old man’s hands slip from the reins. All except one…the favorite son, Brick, is uninterested in anything other than drinking until he gets to that special state of mind. Childless and basically only going through the motions of being married to Margaret due to some previous betrayal and loss, he doesn’t look likely to provide a secure bloodline through which Big Daddy can hand down the property. His older brother and his fecund, scheming wife, do everything they can to get the estate passed to them and to discredit the younger brother.

Big Daddy tries to pull Brick out of his drinking, telling him that “Life is important. There’s nothing else to hold onto. A man that drinks is throwing his life away. Don’t do it, hold onto your life. There’s nothing else to hold onto…” To which Brick retorts, “A drinking man’s someone who wants to forget he isn’t still young an’ believing.”

One of the issues Williams tackles with this play is friendship between men and how it is all too easily assumed to have a homosexual undercurrent to it. Whether or not it did in this particular case, he leaves up to us, but clearly society makes that assumption. As Williams states in his stage notes:

One of the issues Williams tackles with this play is friendship between men and how it is all too easily assumed to have a homosexual undercurrent to it. Whether or not it did in this particular case, he leaves up to us, but clearly society makes that assumption. As Williams states in his stage notes:

The thing they’re discussing, timidly and painfully on the side of Big Daddy, fiercely, violently on Brick’s side, is the inadmissible thing that Skipper died to disavow between them. The fact that if it existed it had to be disavowed to “keep face” in the world they lived in, may be at the heart of the “mendacity” that Brick drinks to kill his disgust with. It may be the root of his collapse. Or maybe it is only a single manifestation of it, not even the most important.

This is part of what drives Brick to drink. He is tormented by his dead friend and the relationship they had. He tries to describe what it was, questioning if it was normal. “Normal? No! –It was too rare to be normal, any true thing between two people is too rare to be normal.” And asking, “Why can’t exceptional friendship, real, real, deep, deep friendship! –between two men be respected as something clean and decent without being thought of as fairies…” It seems we’ve come a long way since the play was written in some ways, and in others not very far at all. Big Daddy doesn’t care so much about all that, especially now that his time is short. He says he’s “Always, anyhow, lived with too much space around me to be infected by ideas of other people. One thing you can grow on a big place more important than cotton! –is tolerance—I grown it.” Good for him, even if he may just be trying to be practical and solve the problem he has at hand.

This is part of what drives Brick to drink. He is tormented by his dead friend and the relationship they had. He tries to describe what it was, questioning if it was normal. “Normal? No! –It was too rare to be normal, any true thing between two people is too rare to be normal.” And asking, “Why can’t exceptional friendship, real, real, deep, deep friendship! –between two men be respected as something clean and decent without being thought of as fairies…” It seems we’ve come a long way since the play was written in some ways, and in others not very far at all. Big Daddy doesn’t care so much about all that, especially now that his time is short. He says he’s “Always, anyhow, lived with too much space around me to be infected by ideas of other people. One thing you can grow on a big place more important than cotton! –is tolerance—I grown it.” Good for him, even if he may just be trying to be practical and solve the problem he has at hand.

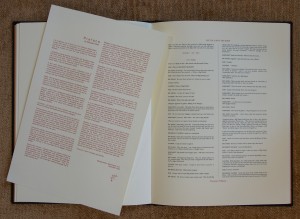

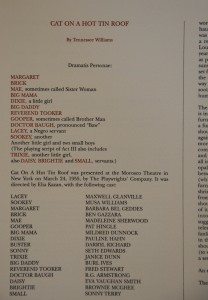

Williams notes that there were two different endings for Cat, and both are wonderful and both are included in this edition. The two Act III’s are described as Cat 1 and Cat 2. Cat 2 was a result of director Elia Kazan’s input on staging the play. The important ending for me, though Williams still leaves it vague in typical fashion, is where it seems that Maggie will get her way. Because after all, “…nothing’s more determined than a cat on a tin roof—is there?”

Williams notes that there were two different endings for Cat, and both are wonderful and both are included in this edition. The two Act III’s are described as Cat 1 and Cat 2. Cat 2 was a result of director Elia Kazan’s input on staging the play. The important ending for me, though Williams still leaves it vague in typical fashion, is where it seems that Maggie will get her way. Because after all, “…nothing’s more determined than a cat on a tin roof—is there?”

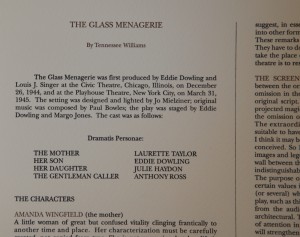

The plays also include some information on the original staging in theater and on film, including the actors that played the roles. One interesting surprise was to see blues-men Sonnie Terry and Brownie McGee playing some of the servants in Cat. I wonder how that came about?

The Glass Menagerie is another beautiful masterpiece. I probably didn’t realize this back when I “had” to read it in high school. Revisiting it for this edition firmly convinces me of its merit and the fact that it richly deserved the fine print treatment that DBS has given it. Laura is such a beautifully tragic heroine. Her disability and shyness set her apart and allow her to live briefly outside of life. For me, Jim’s kiss and then the breaking of the unicorn’s horn are symbolic of her being swept back into the real world from the imaginary safety of her menagerie. Now the unicorn is just like any other horse…and Laura has her hopes of love raised and dashed like the rest of us. But she is left a lesson to learn, if only she can grasp it. Jim tells her: “The power of love is really pretty tremendous! Love is something that—changes the whole world, Laura!” Does she hear it? Williams leaves the result of her transformation vague but there is a sinking feeling that life doesn’t deal kindly with her and her mother after Tom leaves. Tom is also coy about what happened to them; simply stating “I went much further—for time is the longest distance between two places.”

Williams was a master of creating compelling characters, and Amanda is no exception, a driving force through the play even as she is stuck in her past and in her obsession with gentlemen callers. She is unable to understand or recognize her son for what he is and what he wants to be. In one memorable scene admonishing him with “Don’t quote instinct to me! Instinct is something that people have got away from! It belongs to animals! Christian adults don’t want it!” And I got a kick out of the part where she says she returned on of Tom’s books to the library, calling it the one by “that insane Mr. Lawrence.” D.H. Lawrence, I presume?

Williams was a master of creating compelling characters, and Amanda is no exception, a driving force through the play even as she is stuck in her past and in her obsession with gentlemen callers. She is unable to understand or recognize her son for what he is and what he wants to be. In one memorable scene admonishing him with “Don’t quote instinct to me! Instinct is something that people have got away from! It belongs to animals! Christian adults don’t want it!” And I got a kick out of the part where she says she returned on of Tom’s books to the library, calling it the one by “that insane Mr. Lawrence.” D.H. Lawrence, I presume?

As in the other plays, I once again found Williams’ stage directions and commentary particularly interesting. He calls The Glass Menagerie a “memory play” and states that it can therefore be presented with unusual freedom of convention. He also states that “Expressionism and all other unconventional techniques in drama have only one valid aim in drama, and that is a closer approach to the truth.” And, in speaking of the music for the play, Williams states “When you look at a piece of delicately spun glass you think of two things: how beautiful it is and how easily it can be broken. Both of those ideas should be woven into the recurring tune, which dips in and out of the play as if it were carried on a wind that changes. It serves as a thread of connection and allusion between the narrator with his separate point in time and space and the subject of his story. Between each episode it returns as reference to the emotion, nostalgia, which is the first condition of the play. It is primarily Laura’s music and therefore comes out most clearly when the play focuses upon her and the lovely fragility of glass which is her image.” I love it.

As in the other plays, I once again found Williams’ stage directions and commentary particularly interesting. He calls The Glass Menagerie a “memory play” and states that it can therefore be presented with unusual freedom of convention. He also states that “Expressionism and all other unconventional techniques in drama have only one valid aim in drama, and that is a closer approach to the truth.” And, in speaking of the music for the play, Williams states “When you look at a piece of delicately spun glass you think of two things: how beautiful it is and how easily it can be broken. Both of those ideas should be woven into the recurring tune, which dips in and out of the play as if it were carried on a wind that changes. It serves as a thread of connection and allusion between the narrator with his separate point in time and space and the subject of his story. Between each episode it returns as reference to the emotion, nostalgia, which is the first condition of the play. It is primarily Laura’s music and therefore comes out most clearly when the play focuses upon her and the lovely fragility of glass which is her image.” I love it.

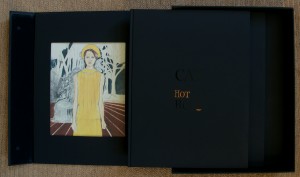

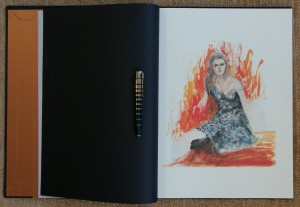

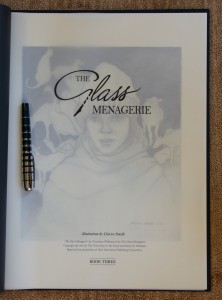

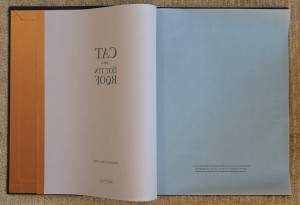

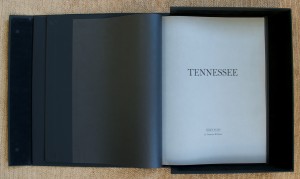

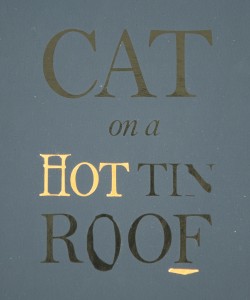

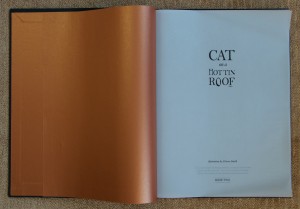

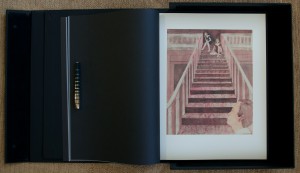

The edition itself is beautiful. The three volumes are hand bound in black and enclosed in a like-bound solander box along with the extra prints of the preface and interview. The inside top cover of the box has one of the prints by Clarice Smith mounted to it. Each volume contains another of her prints at the beginning of the play. Her illustrations really nailed the characters as I saw them in my mind while reading the play. I loved the use of layered opaque paper in front of the print for The Glass

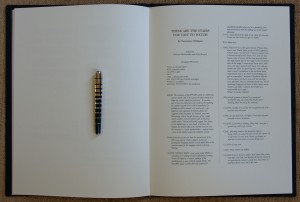

The edition itself is beautiful. The three volumes are hand bound in black and enclosed in a like-bound solander box along with the extra prints of the preface and interview. The inside top cover of the box has one of the prints by Clarice Smith mounted to it. Each volume contains another of her prints at the beginning of the play. Her illustrations really nailed the characters as I saw them in my mind while reading the play. I loved the use of layered opaque paper in front of the print for The Glass  Menagerie volume as well as its use in front of black paper for the title pages. The books are printed letterpress in Florence on a heavy Fabriano Rusticus paper that makes the text look even more 3-dimensional than a lot of letterpress out there. One downside of the paper is that it makes reading a bit difficult, as the pages don’t stay open very easily. Even with the text printed only on the recto side this was a somewhat awkward part of the reading experience. As I’ve raved about in other reviews of dramatic works, I really think the use of multiple ink colors is a nice touch that helps with readability and visual appeal. The books are also quite large at 14” x18”. That makes them probably best read in the safety of the home. They are definitely too large for reading trips out of the house.

Menagerie volume as well as its use in front of black paper for the title pages. The books are printed letterpress in Florence on a heavy Fabriano Rusticus paper that makes the text look even more 3-dimensional than a lot of letterpress out there. One downside of the paper is that it makes reading a bit difficult, as the pages don’t stay open very easily. Even with the text printed only on the recto side this was a somewhat awkward part of the reading experience. As I’ve raved about in other reviews of dramatic works, I really think the use of multiple ink colors is a nice touch that helps with readability and visual appeal. The books are also quite large at 14” x18”. That makes them probably best read in the safety of the home. They are definitely too large for reading trips out of the house.

One other small quibble was a couple of spelling, grammar, and setting errors that I ran across in reading through the volume. But these were few and far enough between that it did not really impact my experience, only providing a momentary and insignificant blip in the pleasure of handling and reading these impressive books.

One other small quibble was a couple of spelling, grammar, and setting errors that I ran across in reading through the volume. But these were few and far enough between that it did not really impact my experience, only providing a momentary and insignificant blip in the pleasure of handling and reading these impressive books.

Overall, the edition was a wonderful way to re-acquaint myself with Tennessee Williams. I will have to seek out more of Williams work as I would like to check out some of this poetry as well. This edition would be a nice addition to your library or collection and would make a striking display on your shelf or table. I’ll also be looking forward to more books from DBS.

AVAILABILITY: This publication was printed in an edition of 1500 and is available directly from DBS Publications, LLC.

NOTE: For some reasons, some of the closeup photos of the book and box covers came out looking grey. I apologize for this misrepresentation of what should show up as deep black covers.

More images: